- Home

- Eoin Colfer

Airman Page 2

Airman Read online

Page 2

When Raymond Trudeau objected to the king’s grant, Henry delivered the often-quoted Trudeau Admonishment.

‘You disagree with an appointee of God Himself,’ Henry is recorded as saying. ‘Perhaps Monsieur Trudeau considers himself above his king. Perhaps Monsieur Trudeau considers himself fit for royal office. So be it. You shall take the Saltee Islands with my blessing, but not as baron. You are their king. King Raymond the First. I will demand neither tithe nor tribute from you or your descendants in perpetuity and, as an added reward, you may wear your crown to my court. Whatever you may find on those most bountiful isles is yours to keep.’

Trudeau could do nothing but bow and stammer his thanks, bitter though the words were. This was a terrible insult, as there was nothing to be found on the Saltee Islands but sea birds and their droppings, and little grew there thanks to the showers of sea spray that coated both islands during rough tides, giving nothing to the Saltees but their name.

But Raymond Trudeau’s fortune was not as bleak as it seemed. Following his effective banishment to the Saltee Islands, a strange glowing cave was discovered by one of his men who was burning gulls from their perches. The cave was a glacial deposit of diamonds. The largest mine ever discovered, and the only mine in Europe. Henry had ordained Raymond Trudeau king of the most valuable estate in the world.

Seven hundred years later and the Trudeau family were still in power in spite of over a dozen invasion attempts from English, Irish and even pirate armies. The famous Saltee walls held fast against cannon, shot and ram, and the celebrated Saltee Sharpshooters were trained to shave the whiskers off a pirate a mile away. There were only two industries on the Saltees. Diamonds and defence.

The Saltee prison was packed to bursting with the foulest dregs of murdering humanity that Ireland and Great Britain had to offer. They worked the diamond mine until they had served their time or died. Most died. A sentence on Little Saltee was a death sentence. Nobody really cared. The Saltees had been making many people rich for centuries, and none of those many people wanted the status quo to change.

Nevertheless change was afoot. Now, there was a new king on the Saltee throne, an American, King Nicholas the First, or Good King Nick as he was known in an increasing number of households. Barely six months in power and already King Nicholas had drastically improved the quality of life for his 3,000 subjects, abolishing taxes and building a modern drainage system, that ran through the town of Promontory Fort on Great Saltee’s northern tip.

When the royal yacht, Razorbill, pulled into Saltee Harbour at dawn after a three-day voyage from France, King Nicholas himself was there to meet her. Truth be told, he did not much look like the other kings of the day, a youthful thirty-seven, dressed in stout hunting leathers and a flat cap. His sideburns were trimmed back, and hair cut military style close to the skull. His face was tanned, with a tic-tac-toe pattern of faded scars on his forehead from a close call with a landmine. A stranger might assume Nicholas to be the king’s gamekeeper, but never the king. There was no pomp or circumstance about the man, and he lived as plainly as one could in a stately palace. Nicholas had served as a skirmisher and a balloonist during the American Civil War, and it was said that he slept on the window seat in his royal chamber because the bed was too soft.

Nicholas was a new breed of European king. One who was determined to use whatever power he had to improve the quality of life for as many people as possible. Good King Nick. Declan Broekhart loved him like a brother.

Declan hitched the yacht’s bowline, then leaped on to the jetty to greet his monarch.

‘Your Majesty,’ he said, bowing slightly.

King Nicholas returned the bow, then punched his friend on the shoulder.

‘Declan! What kept you? I read about your miraculous airborne baby before I see him. I can only pray that he has inherited his mother’s features.’

While the men shared a chuckle, Catherine stepped on to the gangplank, holding her precious bundle wrapped in a blanket.

‘Catherine,’ said Nicholas, taking her arm. ‘Shouldn’t you be resting?’

‘I had my fill of rest on-board.’ Catherine pulled little Conor’s blanket down past his chin. ‘Now, your newest subject would like to meet his king.’

Nicholas peered into the swaddling clothes, finding a baby’s face in the shadows. He was a little disconcerted to find the child’s eyes focused and seemingly taking his measure.

‘Ah,’ he said, rearing back slightly. ‘So… alert.’

‘Yes,’ said Catherine proudly. ‘He has his father’s sharpshooter eyes.’

But King Nicholas saw more.

‘Perhaps. But he has the Broekhart chin too. Stubborn to a fault. Your brow though, Catherine. A scientist perhaps, like his mother.’ He tickled baby Conor’s chin. ‘We need scientists. There’s a new world coming our way from America and Europe too. The Saltees won’t stay independent unless we have something to offer the world, and the diamond mine on Little Saltee won’t last forever. Scientists, that’s what we need here.’ King Nicholas tugged on riding gloves. ‘Teach him well, Catherine.’

‘I will, Your Majesty.’

‘And take him up to the palace. Introduce him to Isabella.’

‘I’ll take him up after breakfast,’ promised Catherine.

Nicholas smiled sadly. ‘Isabella’s mother would have had a gift ready and wrapped. The perfect gift.’ The king stood silently for a moment, remembering his wife, then roused himself. ‘And now, Declan, sorry to drag you away, but apparently some opium smugglers have dug themselves into Lady Walker’s Cave. Right under our noses.’

‘I’ll take care of it, Majesty. Perhaps you would escort Catherine to our quarters?’

‘Nice try, Captain,’ grinned Nicholas, clapping his hands, ‘hoping to keep me out of harm’s way.’ The king was excited again, the old soldier in him relishing the chase. Unlike most old soldiers, he did not relish the kill. These smugglers would be sent to work the diamond mine on the prison island of Little Saltee, but not harmed unless it was unavoidable.

‘Come now, we have dawn light and low tide. Criminals do not like to get up early, so we should catch them napping.’

The king touched his cap to Catherine, then strode off down the jetty towards a small company of Saltee cavalry on horseback. It was, in fact, the entire Saltee Army mounted division. A dozen expert horsemen on Irish stallions. Two of the horses were without riders.

Declan was anxious to stay with his wife, but more anxious to be about his work.

‘I must go, Catherine. The king will injure himself swinging into those caves.’

‘You go, Declan. Keep him safe; the islands need Good King Nick.’

Captain Broekhart kissed his wife and baby, then followed King Nicholas to where the cavalry waited, horses carving spiralled shavings from the jetty planks with their hooves.

‘Your father, the hero,’ Catherine told baby Conor, waving his tiny hand towards Declan. ‘Now, let’s go home and make ready to meet a little princess. Would you like to meet a princess, my stubborn scientist?’

Conor gurgled. It seemed as though he would.

PART 1: BROEKHART

CHAPTER 1: THE PRINCESS AND THE PIRATE

Conor Broekhart was a remarkable boy, a fact that became evident very early in his idyllic childhood. Nature is usually grudging with her gifts, dispensing them sparingly, but she favoured Conor with everything she had to offer. It seemed as though all the talents of his ancestors had been bestowed upon him. Intelligence, strong features and grace.

Conor was fortunate in his situation too. He was born into an affluent community, where the values of equality and justice were actually being applied, on the surface at least. He grew up with a strong belief in right and wrong, which was not muddied by poverty or violence. It was straightforward for the young boy. Right was Great Saltee, wrong was Little Saltee.

It is an easy matter now, to pluck some events from Conor’s early years and say, There it is. The boy wh

o became the man. We should have seen it. But hindsight is an unreliable science and, in truth, there was perhaps a single incident during Conor’s early days at the palace that hinted at his potential.

The incident in question occurred when Conor was nine years old and roaming the serving corridors that snaked behind the walls of the castle chapel and main building. His partner on these excursions was the Princess Isabella, one year his senior and always the more adventurous of the two. Isabella and Conor were rarely seen without each other, and often so daubed with mud, blood and nothing good that the boy was barely distinguishable from the princess.

On this particular summer afternoon, they had exhausted the fun to be had tracking an unused chimney to its source and had decided to launch a surprise pirate attack on the king’s apartment.

‘You can be Captain Crow,’ said little Conor, licking some soot from round his mouth, ‘and I can be the cabin boy that stuck an axe in his head.’

Isabella was a pretty thing, with elfin face and round brown eyes, but at that moment she looked more like a sweep’s urchin than a princess.

‘No, Conor. You are Captain Crow, and I am the princess hostage.’

‘There is no princess hostage,’ declared Conor firmly, worried that Isabella was once again about to mould the legend to suit herself. In previous games, she had included a unicorn and a fairy that were definitely not part of the original story.

‘Of course there is,’ said Isabella belligerently. ‘There is because I say there is, and I am an actual princess, whereas you were born in a balloon.’

Isabella intended this as an insult, but to Conor being born in a balloon was about the finest place to be born.

‘Thank you,’ he said, grinning.

‘That’s not a good thing,’ squealed Isabella. ‘Doctor John says that your lungs were probably crushed by the alti-tood.’

‘My lungs’re better than yours. See!’ And Conor hooted at the sky to show just how healthy his lungs were.

‘Very well,’ said Isabella, impressed. ‘But I am still the princess hostage. And you should remember that I can have you executed if you displease me.’

Conor was not unduly concerned about Isabella having him executed as she ordered him hung at least a dozen times a day and it hadn’t happened yet. He was more worried that Isabella was not turning out to be as good a playmate as he had hoped. Basically he wanted someone who would play the games he fancied playing, which generally involved flying paper gliders or eating insects. But lately Isabella had been veering towards dressing-up and kissing, and she would only explore chimneys if Conor agreed to pretend they were the legendary lovers Diarmuid and Gràinne, escaping from Fionn’s castle.

Needless to say, Conor had no wish to be a legendary lover. Legendary lovers rarely flew anywhere, and hardly ever ate insects.

‘Very well,’ he moaned. ‘You are the princess hostage.’

‘Excellent, Captain,’ Isabella said sweetly. ‘Now, you may drag me to my father’s chamber and demand ransom.’

‘Drag?’ said Conor hopefully.

‘Play drag, not real drag, or I shall have you hung.’

Conor thought, with remarkable wit for a nine-year-old, that if he had actually been hung every time Isabella ordered it, his neck would be longer than a Serengeti giraffe’s.

‘Play drag, then. Can I kill anyone we meet?’

‘Absolutely anyone. Not Papa, though, until after I see how sad he is.’

Absolutely anyone.

That’s something, thought Conor, swishing his wooden sword, thinking how it cut the air like a gull’s wing.

Just like a wing.

The pair proceeded across the barbican, she oohing and he arring, drawing fond but also wary looks from those they passed. The palace’s only resident children were well liked, not at all spoilt, and mannerly enough when their parents were nearby, but they were also light-fingered and would pilfer whatever they fancied on their daily quests.

A certain Italian gold-leaf artisan had recently turned from the cherub he was coating one afternoon to find his brush and tray of gold wafers missing. The gold turned up later coated on the wings of a week-dead seagull that someone had tried to fly from the Wall battlements.

They crossed the bridge into the main keep, which housed the king’s residence, office and meeting rooms. And this would generally have been where the pair would be met with a good-natured challenge from the sentry. But the king himself had just leaned out of the window and sent the fellow running to catch the Wexford boat and put ten shillings on a horse he fancied in the Curracloe beach races. The palace had a telephone system, but there were no wires to the shore as yet, and the booking agents on the mainland refused to take bets over the semaphore.

For two minutes only, much to the princess’s and the pirate’s delight, the main keep was unguarded. They strode in as though they owned the castle.

‘Of course, in real life, I do own the castle,’ confided Isabella, never missing a chance to remind Conor of her exalted position.

‘Arrrr,’ said Conor, and meant it.

The spiral staircase passed three floors, all packed with cleaning staff, lawyers, scientists and civil servants, but through a combination of low infant cunning and luck the pair managed to pass the lower floors to the king’s own entrance: impressive oak double doors with half of the Saltee flag and motto carved into each one. Vallo Parietis read the words. Defend the Wall. The flag was a crest bisected vertically into crimson and gold sections with a white blocked tower stamped in the centre.

The door was slightly ajar.

‘It’s open,’ said Conor.

‘It’s open, hostage princess,’ Isabella reminded him.

‘Sorry, hostage princess. Let’s see what treasure lies inside.’

‘I’m not supposed to, Conor.’

‘Pirate Captain Crow,’ said Conor, slipping through the gap in the door.

As usual, Nicholas’s apartment was littered with the remains of a dozen experiments. There was a cannibalized dynamo on the hearthrug, copper-wiring strands protruding from its belly.

‘That’s a sea creature and those are its guts,’ said Conor, with relish.

‘Oh, you foul pirate,’ said Isabella.

‘Stop your smiling then if I’m a foul pirate. Hostages are supposed to weep and wail.’

In the fireplace itself were jars of mercury and experimental fuels. Nicholas refused to allow his staff to move them downstairs. Too volatile, he explained. Anyway, the fire would only go up the chimney.

Conor pointed to the jars. ‘Bottles of poison. Squeezed from a dragon’s bum. One sniff and you ’vaporate.’

This sounded very possible, and Isabella wasn’t sure whether to believe it or not.

On the chaise longue were buckets of fertilizer, a couple gently steaming.

‘Also from a dragon’s bum,’ intoned Conor wisely.

Isabella tried to keep her scream behind her lips, so it shot out of her nose instead.

‘It’s fert’ lizer,’ said Conor, taking pity on her. ‘For making plants grow on the island.’

Isabella scowled at him. ‘You’re being hanged at sundown. That’s a princess’s promise.’

The apartment was a land of twinklings and shinings for a couple of unsupervised children. A stars-and-stripes banner was draped round the shoulders of a stuffed black bear in the corner. A collection of prisms and lenses glinted from a wooden box closed with a cap at one end, and books old and new were piled high like the columns of a ruined temple.

Conor wandered between these columns of knowledge, almost touching everything, but holding back, knowing somehow that another man’s dreams should not be disturbed.

Suddenly he froze. There was something he should do. The chance may never come again.

‘I must capture the flag,’ he breathed. ‘That’s what a pirate captain is supposed to do. Go to the roof, so I can capture the flag and gloat.’

‘Capture the flag and goat?’

>

‘Gloat.’

Isabella stood hands on hips. ‘It’s pronounced goooaaat, idiot.’

‘You’re supposed to be a princess. Insulting your subjects is not very princessy.’

Isabella was unrepentant. ‘Princesses do what they want – anyway we don’t have a goat on the roof.’

Conor did not waste his time arguing. There was no winning an argument with someone who could have you executed. He ran to the roof door, swishing his sword at imaginary troops. This door, too, was open. Incredible good fortune. On the hundred previous occasions he and Isabella had ambushed King Nicholas, every door in the palace had been locked, and they had been warned by stern-faced parents never to venture on to the roof alone. It was a long way down.

Conor thought about it.

Parents? Flag?

Parents? Flag?

‘Some pirate you are,’ sniffed Isabella. ‘Standing around there scratching yourself with a toy sword.’

Flag, then.

‘Arrr. I go for the flag, hostage princess.’ And then in his own voice, ‘Don’t touch any of the experiments, Isabella. ’Specially the bottles. Papa says that one day the king is going to blow the lot of us to hell and back with his concoctions, so they must be dangerous.’

Conor went up the stairs fast, before his nerve could fail him. It wasn’t far, perhaps a dozen steps to the open air. He emerged from the confines of the turret stairwell on to a stone rooftop. From dark to light in half a second. The effect was breathtaking, azure sky with clouds close enough to touch.

I was born in a place like this, thought Conor

You are a special child, his mother told him at least once a day. You were born in the sky, and there will always be a place for you there.

Conor believed that this was true. He had always felt happiest in high places, where others feared to go.

Artemis Fowl

Artemis Fowl Plugged

Plugged The Opal Deception

The Opal Deception The Arctic Incident

The Arctic Incident The Wish List

The Wish List Novel - Half Moon Investigations

Novel - Half Moon Investigations The Supernaturalist

The Supernaturalist The Lost Colony

The Lost Colony The Artemis Fowl Files

The Artemis Fowl Files The Time Paradox

The Time Paradox The Atlantis Complex

The Atlantis Complex The Eternity Code

The Eternity Code The Time Paradox (Disney)

The Time Paradox (Disney) The Reluctant Assassin

The Reluctant Assassin Artemis Fowl (Disney)

Artemis Fowl (Disney) Highfire

Highfire The Last Guardian

The Last Guardian The Lost Colony (Disney)

The Lost Colony (Disney) Screwed: A Novel

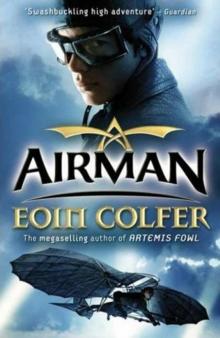

Screwed: A Novel Novel - Airman

Novel - Airman The Forever Man

The Forever Man And Another Thing...

And Another Thing... The Seventh Dwarf

The Seventh Dwarf The Opal Deception (Disney)

The Opal Deception (Disney) The Fowl Twins Deny All Charges

The Fowl Twins Deny All Charges The Last Guardian (Disney)

The Last Guardian (Disney) The Hangman's Revolution

The Hangman's Revolution The Atlantis Complex (Disney)

The Atlantis Complex (Disney) The Eternity Code (Disney)

The Eternity Code (Disney) The Fowl Twins

The Fowl Twins Artemis Fowl. The Arctic Incident af-2

Artemis Fowl. The Arctic Incident af-2 Artemis Fowl and the Atlantis Complex af-7

Artemis Fowl and the Atlantis Complex af-7 Artemis Fowl. The Opal Deception af-4

Artemis Fowl. The Opal Deception af-4 Artemis Fowl. The Lost Colony af-5

Artemis Fowl. The Lost Colony af-5 Airman

Airman Artemis Fowl af-1

Artemis Fowl af-1 Artemis Fowl: The Eternity Code af-3

Artemis Fowl: The Eternity Code af-3 Screwed dm-2

Screwed dm-2