- Home

- Eoin Colfer

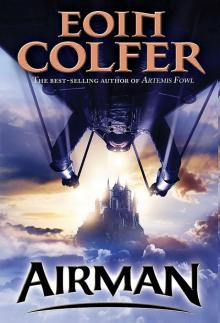

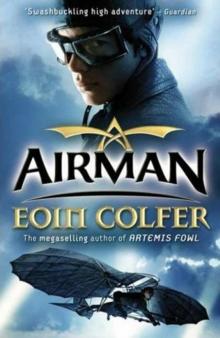

Airman

Airman Read online

Airman

Eoin Colfer

Conor Broekhart was born to fly. In fact, legend has it that he was born flying in a hot air balloon at the world's fair.

In the 1890's Conor and his family live on the sovereign Saltee Islands, off the Irish coast. Conor spends his days studying the science of flight with his tutor and exploring the castle with the king's daughter, Princess Isabella.

But the boy's idyllic life changes forever the day he discovers a conspiracy to overthrow the king. When Conor tries to expose the plot, he is branded a traitor and thrown into jail on the prison island of Little Saltee. There, he has to fight for his life as he and the other prisoners are forced to mine for diamonds in inhumane conditions.

There is only one way to escape Little Saltee, and that is to fly. So he passes the solitary months by scratching drawings of flying machines into the prison walls. The months turn into years, but eventually the day comes when Conor must find the courage to trust his revolutionary designs and take to the skies.

Eoin Colfer

Airman

Copyright © Eoin Colfer, 2008

For Declan Dempsey

PROLOGUE

Conor Broekhart was born to fly, or more accurately he was born flying. Though Broekhart’s legend is littered with fantastical stories, the tale of his first flight in the summer of 1878 would be the most difficult to believe, had there not been thousands of witnesses. In fact, an account of his birth in a hot-air balloon can be read in the archives of the French newspaper, Le Petit Journal, available to all for a small fee at the Librairie Nationale.

Above the article, there is a faded black-and-white photograph. It is remarkably sharp for the period, and was taken by a newspaperman who happened to be in the Trocadéro gardens at the time with his camera.

Captain Declan Broekhart is easily recognizable in the picture, as is his wife, Catherine. He, handsome in his crimson-and-gold Saltee Island Sharpshooters uniform, she shaken but smiling. And there, protected in the crook of his father’s elbow, lies baby Conor. Already with a head of blond Broekhart hair and his mother’s wide, intelligent brow. No more than ten minutes old and through some trick of the light or photographic mishap, it seems as though Conor’s eyes are focused. Impossible of course. But imagine if somehow they had been, then baby Conor’s first sight would have been a cloudless French sky flashing by. Little wonder he became what he became.

Paris, summer of 1878

The World Fair was to be the most spectacular ever seen, with over 1,000 exhibitors from every corner of the world.

Captain Declan Broekhart had travelled to France from the Saltee Islands at his king’s insistence. Catherine had accompanied him at her own request, as she was the scientist in the family and longed to see for herself the much heralded Galerie des Machines, which showcased inventions promising to make the future a better one. King Nicholas had sent them to Paris, to investigate the possibility of a balloon division for the Saltee Wall.

On the third day of their trip, the pair took a buggy along the Avenue de l’Opéra, to observe the Aeronautical Department’s balloon demonstration in the Trocadéro gardens.

‘Do you feel that?’ asked Catherine. She took her husband’s hand, and placed it on her stomach. ‘Our son is kicking to be free. He longs to witness these miracles for himself.’

Declan laughed. ‘He or she will have to wait. The world will still be here in six weeks.’

When the Broekharts arrived at the Trocadéro gardens, they found the Aeronautical Squadron in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, or rather that of her head. The statue would be presented to the United States when completed, but for now Lady Liberty’s head alone was being showcased. The copper structure dwarfed most of the fair’s other exhibits and it was amazing to imagine how colossal the assembled statue would be when it finally stood guard over New York City’s harbour.

The Aeronautical Squadron had inflated a dirigible balloon on a patch of lawn, and was politely holding the crowd back with a velvet rope. Declan Broekhart approached the soldier on sentry duty and handed him his sealed letter of introduction from the French ambassador to the Saltee Islands. Within minutes they were joined by the squadron’s captain, Victor Vigny.

Vigny was lithe and tanned with a crooked nose and a crown of jet-black hair that stood erect on his scalp like the head of a yard brush.

‘Bonjour, Captain Broekhart,’ he said, removing one white glove and shaking the Saltee Island officer’s hand warmly. ‘We have been expecting you.’ The Frenchman bowed deeply. ‘And this must be Madame Broekhart.’ Vigny checked the letter in mock confusion. ‘But, madame, nowhere here does it say how beautiful you are.’

The Frenchman’s smile was so charming that the Broekharts could not take offence.

‘Well, Captain,’ said Vigny, sweeping back his arm dramatically to introduce his balloon. ‘I give you Le Soleil, the Sun. What do you think of her?’

The dirigible was undeniably magnificent. An elongated golden envelope swaying gently over its leather-bound basket. But Declan Broekhart was not interested in decoration, he was interested in specification.

‘A bit more pointed than others l’ve seen,’ he noted.

‘Aérodynamiqué,’ corrected Vigny. ‘She glides across the sky like her namesake.’

Catherine unhooked herself from her husband’s arm.

‘A cotton-silk blend,’ she said, craning her head back to squint at the balloon. ‘And twin screws on the basket. A neat piece of work. How fast does she travel?’

Vigny was surprised to hear such technical observations from a female, but he disguised his shock with a few rapid blinks, then smoothly delivered his answer.

‘Ten miles an hour. With the help of God and a fair wind.’

Catherine peeled back a corner of leather, revealing the woven basket underneath.

‘Wicker and willow,’ she said. ‘Makes a nice cushion.’

Vigny was enchanted. ‘Yes. Absolument. This basket will last for five hundred hours in the sky. French baskets are the best in the world.’

‘Très bien,’ said Catherine.

She hoisted her petticoats and climbed the wooden steps to the basket, displaying remarkable agility for a woman eight months’ pregnant. Both men stepped forward to object, but Catherine did not give them time to speak.

‘I dare say I know more about the science of aeronautics than both of you. And I really don’t think I have crossed the Celtic Sea to stand in a glorified field while my husband experiences one of the wonders of the world.’

Catherine was perfectly calm as she made this statement, but only a dullard could have missed the steel in her voice.

Declan sighed. ‘Very well, Catherine. If Captain Vigny permits it.’

Vigny’s only answer was a Gallic shrug that said, Permit it? I pity the man who tries to stand in this woman’s way.

Catherine smiled.

‘Very well, it is settled. Shall we cast off?’

Le Soleil loosed its anchors shortly before three that afternoon, quickly climbing to a height of a few hundred feet.

‘We are in heaven,’ sighed Catherine, clutching her husband’s hand tightly.

The young couple looked upwards into the belly of the balloon itself. The silk was set shimmering by the breeze and sparkling by the sun. Golden waves billowed across its surface, rumbling like distant thunder.

Below them the Trocadéro gardens were emerald lakes, with Lady Liberty’s head breaching the surface like a Titan of legend.

Vigny fed a small steam engine, sending power to the twin propellers. Fortunately, the prevailing wind snatched the smoke away from the basket.

‘Impressive, non?’ shouted the Frenchman above the engine’s racket. ‘How many are you thinking of ordering?’

&

nbsp; Declan pretended not to be impressed. ‘Perhaps none. I don’t know if those little propellers would have any effect against an ocean wind.’

Vigny was about to argue the merits of his steam-powered dirigible when a sharp flat crack echoed across the skies. It was a noise familiar to both soldiers.

‘Gunshot,’ said Vigny, peering towards the ground.

‘Rifle,’ said Declan Broekhart grimly. As captain of the Saltee Sharpshooters he knew the sound well. ‘Long range. Maybe a Sharps. See, there.’

A plume of grey-blue smoke rose into the sky from the western border of the gardens.

‘Gun smoke,’ noted Vigny. ‘One cannot help wondering who the target might be.’

‘No need to wonder, monsieur,’ said Catherine, her voice shaking. ‘Look above you. The balloon.’

Both men searched the golden envelope for a puncture. Both found one. The bullet had entered through the lower starboard quadrant and exited through the upper port section.

‘Why are we not dead?’ wondered Declan.

The bullet was not enough to ignite the hydrogen,’ explained Vigny. ‘An incendiary shell would have done so.’

Catherine was badly shaken. For the first time in her short life, mortality was at hand, and not just her own. By stepping into the balloon’s basket she had put her child’s life at risk. She folded her arms across her stomach.

‘We must descend. Quickly. Before the envelope rips.’

In the fraught minutes that were to follow, Vigny proved his skill as an aeronaut. He perched on the basket’s lip, gripping a stanchion in one hand and the gas-release line in the other. With a tap of his boot he pushed the tiller wide. Le Soleil swung in a gentle arc. Vigny intended to set her down inside the velvet rope.

Declan Broekhart stayed at his wife’s side. Strong and stubborn as Catherine was, the gunshot had shocked her system. This had the effect of bringing forward her child’s due time. The body realized that it was in mortal danger, so the best chance for the baby was in the wide world.

A spasm of pain buckled Catherine’s knees. She collapsed backwards, cradling her stomach.

‘Our son is coming,’ she gasped. ‘He refuses to wait.’

Vigny almost fell off his perch. ‘Mon Dieu. But, madame, this is impossible. I cannot allow it on my ship. I do not even know if this is good luck or bad luck. I will have to check the aeronaut’s manual. It would not surprise me if we had to sacrifice an albatross.’

It was Vigny’s habit to chatter wittily when anxious. Wit in times of danger was, in his opinion, very cavalier. This did not stop him performing his duties. He guided the dirigible expertly towards the chosen landing spot, compensating for the leaks with expert tugs on the gas line.

On the basket’s cramped floor, Catherine struggled to deliver her child. Her leg shot out involuntarily as the pain hit. The stroke was a lucky one, catching her husband on the shin and snapping him out of his near panic.

‘What can I do, Catherine?’ he asked, keeping his voice steady, his tone light, as though giving birth in a falling balloon was the most natural thing in the world.

‘Hold me steady,’ replied Catherine through gritted teeth. ‘And give me your weight to push against.’

Declan did as he was told, calling over his shoulder to Vigny.

‘Steady. Keep her steady, man.’

‘Talk to the Almighty,’ retorted Vigny. ‘He is sending the gusts of wind, not I.’

They were in reasonably good order. The envelope was damaged, but holding her integrity. The Broekharts huddled on the floor, engrossed in the business of bringing life to the world.

They would have made it. Vigny was already imagining the first sip of the champagne he planned to order the moment his feet touched solid ground, when the air was split with a brace of gunshots. Both bullets pierced the balloon, and this time their effect was more severe. One passed straight through as its predecessor had, but the second clipped a seam, sending a rip racing to the crown of the balloon. Air and gas screamed from the distressed dirigible like a company of banshees.

Vigny pitched forward into the basket, bouncing off Declan Broekhart’s broad back. They were in God’s hands now. With the envelope so grievously ruptured, the Frenchman could not claim a single degree of control over the balloon’s path. They dropped rapidly, the deflating envelope flapping above them.

Catherine and Declan ignored their own fates, concentrating on their child’s.

‘I see the baby,’ said Declan, shouting into the wind. ‘Almost there, my darling.’

Catherine Broekhart held back the despair clamouring in her mind and pushed her baby into the world. He arrived without a cry, reaching out to grip his father’s finger.

‘A boy,’ he said. ‘My strong son.’

Catherine gave herself not a minute to recover from her brief labour. She leaned forward and grasped her husband’s lapel.

‘You cannot let him die, sir.’ It was an order, plain and simple.

Vigny swaddled the newborn in his blue Aeronautical Squadron jacket.

‘We can but pray,’ he said.

Declan Broekhart climbed to his feet, taking in the literal gravity of their situation at a glance. The basket was in virtual freefall now, slicing east directly towards Lady Liberty’s head. Any considerable impact would surely result in the baby’s death, and he had been forbidden to allow that. But how to avoid it?

Fortune saved them, at least temporarily. The envelope spent its last breath, then impaled itself on the third and fourth rays of Liberty’s crown. The material ripped, bunched and jammed between the rays, halting the basket’s murderous descent.

‘Providence,’ breathed Captain Broekhart. ‘We are spared.’

The basket swung like a pendulum, grazing the lower curve of Lady Liberty’s cheek with each pass. The copper bust rang, attracting gawkers like church worshippers. Catherine held on to her baby son, absorbing the impact as best she could. The envelope’s threads popped with cracks like gunfire.

‘The balloon will not hold,’ said Vigny. ‘We are still twenty feet up.’

Declan nodded. ‘We need to lash her to the statue.’ He grabbed Le Soleil’s anchors, tossing one to Vigny. ‘A case of the finest red wine if you make the shot.’

Vigny tested the anchor’s weight. ‘Champagne, if you don’t mind.’

Both men threw their anchors high between the last two rays of Lady Liberty’s crown. Their aim was true and the anchors bumped the statue’s ringlets, then slid back down, raising sparks as the metal surfaces cracked together. The anchors bit on both sides of the crown and stuck fast. Declan and Vigny quickly pulled a loop of rope through the basket’s bow and stern rings, cinching them tight.

Not a moment too soon. With the screech of a seabird, the balloon material ripped itself free of the statue’s crown, dropping the basket a further stomach-lurching yard until the anchor ropes took the strain. The ropes groaned, stretched and held.

‘My basket is now a cradle for your baby,’ panted Vigny, and then, ‘Champagne. A case. The sooner the better.’

Declan squatted below the basket’s rim, tugging the Frenchman’s cuff until he too bent low.

‘Your hunter may have more bullets to spend,’ he said.

‘True,’ agreed Victor Vigny. ‘But I think he will have fled. We no longer present such an enormous target, and by now the gendarmes will be on his trail. I imagine it was an anarchist. They have been making threats.’

In the Trocadéro gardens, the entire crowd had pooled below the basket. They had come to the World Fair expecting spectacle, but here was high adventure. The Aeronautical Squadron leaned long ladders against the wicker basket to rescue Le Soleil’s stranded passengers. Catherine climbed down first, aided by the gallant Captain Vigny. Then came the proud father, cradling the miraculous baby in his arms. People gasped and surged forward. A child. There had been no child in the basket when it took flight. It was as if the world had never before seen a baby.

Bo

rn in the sky. Imagine it. A child of wonder.

Ladies and gentlemen elbowed each other shamelessly, longing for a glimpse of his cherubic face.

Look, the eyes are open. His hair is almost white. Perhaps the altitude?

Someone popped the cork on a bottle of champagne, and an Italian count passed around Cuban cigars. It was as if the entire assembly were celebrating the baby’s survival. Vigny snagged the bottle, quaffing deeply.

‘Perfect,’ he sighed, passing it to Declan Broekhart.

‘He is a charmed boy. What will you call him?’

Broekhart grinned, deliriously happy.

‘I thought perhaps Engel. He came from the skies, after all. And our family name is Flemish.’

‘No, Declan,’ said Catherine, stroking her son’s white-blond hair. ‘Though he is an angel, he has my father’s brow. Conor is his name.’

‘Conor?’ said Declan, in mock protest. ‘Irish from your family. Flemish from mine. The boy is a mongrel.’

Vigny lit two cigars, passing one to the proud father. ‘Now is not the time to argue, mon ami.’

Declan nodded. ‘It never is. Conor he shall be called. A strong name.’

Vigny bonged a knuckle on Lady Liberty’s chin. ‘Whatever he is called, this boy is indebted to Liberty.’

This was the second omen of the day. Conor Broekhart would eventually pay his debt to liberty. The first omen was, of course, the airborne birth. Perhaps he would have been a sky pilot even without Le Soleil, or perhaps something was awakened in him that day. An obsession with the sky that would consume Conor Broekhart’s life, and the lives of everyone around him.

And so a few days after Conor’s famous birth, Captain Declan Broekhart and his family sailed from France back to the tiny sovereign state of the Saltee Islands off the Irish coast.

The Saltee Islands had been ruled by the Trudeau family since 1171 when England’s King Henry II had given them to Raymond Trudeau, a powerful and ambitious knight. It was a cruel joke as the Saltee Islands were little more than gull-infested rocks. By placing Trudeau in charge of the Saltee Islands, Henry fulfilled his contract of granting his knight an Irish estate, but also made it clear what happened to overly ambitious knights.

Artemis Fowl

Artemis Fowl Plugged

Plugged The Opal Deception

The Opal Deception The Arctic Incident

The Arctic Incident The Wish List

The Wish List Novel - Half Moon Investigations

Novel - Half Moon Investigations The Supernaturalist

The Supernaturalist The Lost Colony

The Lost Colony The Artemis Fowl Files

The Artemis Fowl Files The Time Paradox

The Time Paradox The Atlantis Complex

The Atlantis Complex The Eternity Code

The Eternity Code The Time Paradox (Disney)

The Time Paradox (Disney) The Reluctant Assassin

The Reluctant Assassin Artemis Fowl (Disney)

Artemis Fowl (Disney) Highfire

Highfire The Last Guardian

The Last Guardian The Lost Colony (Disney)

The Lost Colony (Disney) Screwed: A Novel

Screwed: A Novel Novel - Airman

Novel - Airman The Forever Man

The Forever Man And Another Thing...

And Another Thing... The Seventh Dwarf

The Seventh Dwarf The Opal Deception (Disney)

The Opal Deception (Disney) The Fowl Twins Deny All Charges

The Fowl Twins Deny All Charges The Last Guardian (Disney)

The Last Guardian (Disney) The Hangman's Revolution

The Hangman's Revolution The Atlantis Complex (Disney)

The Atlantis Complex (Disney) The Eternity Code (Disney)

The Eternity Code (Disney) The Fowl Twins

The Fowl Twins Artemis Fowl. The Arctic Incident af-2

Artemis Fowl. The Arctic Incident af-2 Artemis Fowl and the Atlantis Complex af-7

Artemis Fowl and the Atlantis Complex af-7 Artemis Fowl. The Opal Deception af-4

Artemis Fowl. The Opal Deception af-4 Artemis Fowl. The Lost Colony af-5

Artemis Fowl. The Lost Colony af-5 Airman

Airman Artemis Fowl af-1

Artemis Fowl af-1 Artemis Fowl: The Eternity Code af-3

Artemis Fowl: The Eternity Code af-3 Screwed dm-2

Screwed dm-2