- Home

- Eoin Colfer

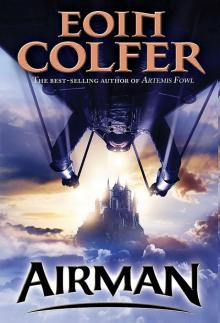

Novel - Airman Page 22

Novel - Airman Read online

Page 22

He stood and ran across the Wall walk. His footsteps seemed absurdly loud as his boots clacked on the stone.

Surely the sounds would march along the Wall to the guard’s tower. Concentrate on your actions. The slightest slip could be the death of you.

It was curious, but sometimes the voice in Conor’s mind sounded like Victor Vigny. I have a guardian angel, and he is French. This made him grin, and so in spite of the life or death situation, it was a smiling Conor Finn who hoisted himself onto the Little Saltee parapet and launched himself into the night sky. I am flying home.

Sebber Bridge, Great Saltee

Pike generally worked the early shift on Little Saltee, then spent sunlight hours and leisure days on the big island, nursing his one-legged mother and fixing the cottage wall, which he had been working on now for fifteen years. When he wasn’t mixing mortar for the wall, Pike was making himself money hand over fist selling information to the Battering Rams.

Pike was never going to be in the gang’s inner circle, but he was a useful man in any situation because, in spite of his apparent lack of gray matter, he had an uncanny knack for accumulating information. The warden, a political man, appreciated this and granted Pike extra leave time to hook him any court gossip he could, while the Battering Rams paid him handsomely for any customs information he was able to wheedle from his mates on the docks. Two bags of coin per week, and neither party any the wiser.

As well as gathering information, Pike ran the odd errand for the Rams. Nothing violent that could see him hanged— and also he was an inveterate coward. His latest job was simplicity itself, if a little puzzling. Until further notice, on any night there was a stiff breeze from the mainland, he was to tow a skiff around to Sebber Bridge and leave it there. Simple as that. Beach the boat on the shale outcrop below Promontory Fort, then row back up the coast to the harbor. No lights, no whistling nor singing sea shanties, or the Wall Sharpshooters would put a bullet in his behind. Simply beach the boat and go. The skiff would make its own way back to Saltee Harbour the next day.

Simple orders, but not to Pike’s taste. Thanks to his double pay packet, he was well aware just how valuable good information was, and he felt certain that there were those who would pay to know what manner of person was picking up a skiff on Sebber Bridge in the wee hours. Not someone on the up and up, that was for certain. Honest citizens came and went through the harbor without the need for skulduggery like this. The trick was how to sell the information without falling foul of the Battering Rams. But he could chew on that problem when he had some information to sell.

So Pike decided to delay his departure awhile, until the mystery sailor had set sail. Then he would know what kind of a nugget he had, and how much it was worth. He concealed his own punt under a bank of weed, then crawled high into the rocks and settled in to wait. After a couple of hours, he was regretting not bringing more tobacco along, and was considering stuffing his pipe with seaweed, when something whooshed overhead, causing him to drop his pipe altogether.

If that was a bat, then it was a big one. Low-flying gull, more like, or a kestrel over from the mainland. Pike had a vague sense of the creature’s bigness. There would be some eating in a bird like that. A pity I don’t have my slingshot along. Even a gull can taste passable when you cook it right.

He wriggled forward out of his crevasse just in time to see a man with wings swoop in to land on Sebber Bridge, his heels dragging up arcs of shingle. A flying man, he thought, flabbergasted. A man that can fly.

Pike knew instantly that this was the most valuable thing he would ever see. He pulled a pad from his pocket, licking the stub of a pencil that hung from a string on the binding. A good tout never knows when a nugget will need recording. Keep your pencil close to your heart, and you’ll never miss a trick.

So, with his heart rattling his ribs and his fingers shaking, Pike sketched the winged airman hanging on to the skiff ’s gunwale, lest the breeze carry him off to the moon. He drew arrows pointing to the wings, and above the arrows wrote wings, as if writing the word made what was before his eyes more believable. He noted it down when the airman pulled a lever and his wings were hoisted behind him. He drew a diagram of the harness and how it cradled the sky rider from shoulder to knee. He saw how the man took himself out of the harness like a lady from her bodice, and collapsed the whole contraption down by pulling out a few stays till the wings folded up neater than a picnic blanket.

Perhaps I should just take those wings, thought Pike. That airman don’t look so big. I could part his ribs with my knife and present those wings to the warden. Perhaps that would be the best course of action.

But then he noticed a saber on the man’s belt, and a revolver on his other hip. There was also the possibility that these airman types possessed strange mystical powers such as the evil eye, or the deathly hex. Best leave it at pictures for today, he decided. Next time I will be prepared, and he will be relaxed. A nice short-handled ax should do the trick.

The airman stowed his gear neatly under the aft seat, then dug his toes into the shale, pushing off. The skiff slid sweetly into the dark water with no more of a splash than the waves were making on the north shore.

He’s gone, thought Pike. I am safe. Perhaps he thought his thoughts too loudly, because the airman froze and turned his glass-goggled eyes toward the rocks. His head was cocked like a puzzled deer’s, and he scanned the higher levels with twin orange circles.

His eyes are on fire, thought Pike. He can see in the dark.

But the strange flying man turned, leaping neatly into the skiff, his landing sending her scudding out across the water, prow slapping the waves. In seconds the dark sail unfurled, and she tacked to starboard, wide of the island.

Pike sighed in relief. Perhaps a short-handled ax will not do the job, he decided. Perhaps I need something with a long handle.

CHAPTER 13: THE SOLDIER’S RETURN

Kilmore

Conor tacked wide, riding the offshore wind as far as possible, before dropping sail and rowing toward Kilmore Harbour. The clouds had thickened, and a few spatters of rain knocked on the planking. The tide was on the rise, so he made good time in spite of the wind on his back.

Conor had expected to feel elated at this moment; he had been wishing for it long enough. There were diamonds at his belt and freedom in his future. Zeb Malarkey had sent him new papers, so he could buy Otto’s freedom, then book passage to New York and start his life anew.

He did feel a certain satisfaction, but it was grim and muted. It seemed as though memories of his old life were reclaiming their place at the forefront of his mind, now that he was out of prison.

Conor wondered if he could ever feel true joy again, without his loved ones to share his accomplishments. He allowed himself a brief daydream. He imagined landing his glider not on Little Saltee, but on the long mainland beach of Curracloe, which ran straight and flat for several miles. This was the spot where Victor had incessantly talked of testing their aeroplanes.

There would be crowds present, of course, and journalists from all over the world. Gaggles of skeptical scientists, too. But Conor did not care a fig for any of them; he was on the lookout for his parents, and Victor. They would be hugging each other with excitement and pride. His father would reach him first as he swooped in to land. Perhaps Isabella would attend.

His heart sank. Isabella. She believes that I helped to kill her father. How could she believe that?

Instead of gliding onto the golden sands of Curracloe, he was alone in a boat, with no one to boast to. No one to celebrate with. The power of flight was no longer an achievement in itself, it was a way to aid him in his thievery. I have flown farther than any other man. I have flown over water at night. No one to tell but the stars. The only person who knows is a cruel prison guard. A buffoon who thinks that I am the devil. I am the world’s first flying thief.

Conor shook his head to dislodge these disquieting thoughts, then threw his back into the oars. He sculled skil

fully, as his father had taught. Bend forward, dip the blades but not too deep. Pull with the back and then arms. Develop a rhythm and let that rhythm calm you. A man can be truly at peace on the water in a small boat, even though only a plank of wood separates him from the cold, unforgiving ocean. Can a thief be at peace? For a time, perhaps.

Conor tied the skiff off at the quay, stuffed his hat and goggles into a jacket pocket, then draped the coat over the folded glider. He hefted the nondescript package onto his back and climbed the ladder to the pier. The diamonds clinked like bags of marbles with each step he took along the quay wall. He hailed two boys patching a net on the slip and gave them two shillings. One for the ferry back, and the other for yourselves.

It was common for visitors to the Saltee Islands to have one tankard too many and miss the last ferry. Common enough not to raise suspicions. There were always a couple of boys on the docks willing to return a borrowed boat, for a fee, naturally.

I may have need of these boys a few nights more, thought Conor. Then I leave this place forever.

But there was no relish in the thought. As thoughts of his family grew stronger, his dream of America had paled. Nevertheless he would persevere, as staying here, close enough to home to see the kitchen light burning, would be intolerable. I am Conor Finn now. I have no family.

Kilmore village was quiet enough, due to the lateness of the hour, though there was still some ruckus emanating from the doorway of the Wooden House, the local pub built almost entirely from the deckhouse of a sunken Greek ship.

Conor was tempted to go inside and sit himself down with a bowl of stew, but the cargo on his back and belt was too valuable to stow under a tavern table, so he trudged on up the hill, leaving the village behind.

His new home was two miles past the village, off the old coast road. Conor climbed a stile and followed a worn path along the cliff edge to a set of late medieval gates, with eagles perched on their mossy pillars. Eagles, thought Conor. Victor’s little joke.

The wrought iron gates were imposing enough, and might have deterred thieves had not the walls on either side been cannibalized by locals over the years to build their dwellings. Cut stone is not so cheap that it can be left piled high in a derelict estate. There was no more than odds and halves left now littering the grass.

Conor stepped over the broken wall, walking along an avenue that wound through a copse of willow trees. Behind this screen stood a Martello tower, a squat cylinder of stone with walls of a prodigious thickness, built by the British army to keep an eye on the Saltee Islands. The single door was eight feet from the tower’s base and could only be reached by ladder, and the windows were letter-box gun ports that would allow the garrison stationed inside to pick off any poor unfortunates unlucky enough to be on the offensive.

Conor disentangled a ladder from the weeds at the base of the tower and propped it up against the tower wall; then, balancing the weight of the collapsed glider on his shoulder, he edged slowly up the rungs.

A pity to survive night flights over St. George’s Channel only to crack my skull falling from a ladder.

The door seemed flimsy, of dry, crumbling wood held together by rivets and steel bands, but there were many deceptive things about this tower. Conor had spent many hours working on the structure, almost exclusively on the inside. No need to advertise the renovations. A steel door lay behind the wooden one, housed in a reinforced frame. Conor threaded a key through the lock and let himself in.

He sighed in almost unconscious relief as he locked the door behind him.

Home. Alive.

The inside was far more salubrious than the exterior suggested. On the first story was a fully equipped laboratory for the study of aeronautics, with more advanced machinery than would be found in many a royal college. Charts were nailed to the walls: the theories and diagrams of da Vinci, Cayley, the Marquis de Bacqueville. Models of gliders to various scales hung from the ceiling beams. Tires, tubes, wings, engines, oil drums, timber planks, frames, and reams of fabric were stacked neatly around the walls; baskets of reeds, ball bearings, magnets, rivets, and screws lay neatly in wooden bowls on the long bench. On a steam winch platform to the roof sat rifles, revolvers, swords, two small caliber cannons, and a pyramid of cannonballs. Victor had been preparing for a battle. He knew Bonvilain wanted him dead.

A Corsican tower at Mortella Point had once withstood bombardment from two British warships for almost two days with the loss of only three men. The British had copied the design and misspelled the name, changing Mortella to Martello. If Bonvilain wished to gain entry to La Brosse’s laboratory, he would have to pay dearly for the privilege.

It had not been difficult for Conor to locate the tower Victor had told him about on the last day of his life. There were two Martello towers in the vicinity of Kilmore, and one had been occupied for the past fifty years. That left the gloomily named Forlorn Point. The tower had originally been called simply Saltee Watch, but the men of the garrison stationed there had soon taken to calling the tower after the headland it stood on. A name more in tune with the unrelenting winds and typical leaden weather of the region than the almost cheery sounding Saltee Watch. So Forlorn Point it became, made somewhat notorious by the folk singer Tam Riordan in his “Lament of Forlorn Point,” which began: “’Tis off I am to Forlorn Point for my sins.” The second line was no jollier: “And if there’s a tide, I aim to throw myself in. . . .”

It was said that the tower was haunted by the ghosts of thirty-seven men who were burned alive inside its walls when the armory caught fire. No wonder it slid into dereliction.

That is, until Victor Vigny decided that it would make an ideal workshop and persuaded King Nicholas to fund the project. The Frenchman purchased the tower in his own name, to hide Nicholas’s involvement, then had a series of shipments sent there from London, New York, and even China.

The materials had been winched to the roof and then humped downstairs to the laboratory floor, and there they had lain for two years, undisturbed by the drunken local caretaker, until Conor arrived to find a key waiting for him in the talons of the pillar’s stone eagle.

Conor was not worried about the ghosts; indeed he was thankful for the legend, as it kept the superstitious locals away. Once in a while a lad would bring his girl as far as the tower wall so they could touch the clammy stones then run away squealing, but besides those minor intrusions, he was left alone.

He was civil in the village, but did not invite friendship. He bought his supplies, paid with coin, and went on his way. The locals were not sure what to make of the pale, blond, young man living at Forlorn Point.

He walks like a fighter, some said. Always ready to draw that saber of his.

Handsome but fierce, concluded the women.

One girl disagreed. Not fierce, she said. Haunted.

The innkeeper had chuckled. Well, if it’s haunted Mister Handsome-but-Fierce wants, he’s in the right place.

Conor’s living quarters were underneath the laboratory on ground level, but he did not spend much time down there, as the gloomy enclosure reminded him of his cell on Little Saltee. Victor had equipped it luxuriously with a four-poster bed, bureau, and chaise longue. There was even a toilet plumbed down to the ocean; but when the lights went out and the walls juddered with every wave crash, Conor was transported back to Little Saltee. Each morning he was woken by the booming cannon shot from the prison, and one night he found himself almost unconsciously scratching some calculations into the wall with a sharp stone. It was difficult enough living in such proximity to home, he decided, without re-creating his prison cell here on the mainland.

And so he slept on the roof, or rather, what had been the roof but was now an extra level, Victor’s pièce de résistance. Martello towers were constructed with completely flat roofs that could bear the weight of two cannons and the men to operate them. Victor had used this strength and flatness as a base for a powerful wind tunnel, driven by four steam-powered fans. For years, they had been fo

rced to study the effects of wind over wing surfaces using a whirling-arm device, but now lift, drag, and relative air velocity could be accurately measured using the most powerful wind tunnel in the world. The device was unsophisticated but effective. Twenty feet long and twenty-five feet square, it was powered by a steam-injection system that was capable of producing a flow velocity of sixty miles per hour.

With this tunnel, Conor had learned that many of his prison designs were flawed, and that many more showed promise. Four of his gliders had made it past the model stage, and he was convinced that his engine-powered aeroplane would fly, too, when he put it together.

There was another use for the wind tunnel. Conor used it to augment his launch from the tower roof. He would hitch himself up, spread his wings, then duck obliquely into the wind stream, to be propelled into the sky as though shot from a cannon.

You are taking risks, Victor would have undoubtedly said. Leapfrogging over several steps in the scientific process. And your records are vague and often coded. What manner of scientist are you?

I am no more a scientist, Conor would have replied. I am an airborne thief.

That morning he sat on the roof, back resting against the wind tunnel’s planking, swaddled in a woolen blanket and eating from a can of beef. The rising sun cast a golden glow over the distant Saltee Islands, as though they were some kind of magical place. Mystical islands.

He thought of his parents and of Isabella; then, in a fit of irritation, sent his fork sparking across the stone roof and tramped down the stairs to the lower level. I will sleep below and be reminded of my cell. I need strength of purpose.

Two days later, Conor had finished repairing the wind tunnel planks and made the trip to Kilmore. He fancied a cooked meal and to hear the voices of others even if they were not addressing him. It had come as something of a shock to him when he realized that his loneliness had intensified since escaping from prison. It was necessary for him to seek out the company of men, for the sake of his own sanity.

Artemis Fowl

Artemis Fowl Plugged

Plugged The Opal Deception

The Opal Deception The Arctic Incident

The Arctic Incident The Wish List

The Wish List Novel - Half Moon Investigations

Novel - Half Moon Investigations The Supernaturalist

The Supernaturalist The Lost Colony

The Lost Colony The Artemis Fowl Files

The Artemis Fowl Files The Time Paradox

The Time Paradox The Atlantis Complex

The Atlantis Complex The Eternity Code

The Eternity Code The Time Paradox (Disney)

The Time Paradox (Disney) The Reluctant Assassin

The Reluctant Assassin Artemis Fowl (Disney)

Artemis Fowl (Disney) Highfire

Highfire The Last Guardian

The Last Guardian The Lost Colony (Disney)

The Lost Colony (Disney) Screwed: A Novel

Screwed: A Novel Novel - Airman

Novel - Airman The Forever Man

The Forever Man And Another Thing...

And Another Thing... The Seventh Dwarf

The Seventh Dwarf The Opal Deception (Disney)

The Opal Deception (Disney) The Fowl Twins Deny All Charges

The Fowl Twins Deny All Charges The Last Guardian (Disney)

The Last Guardian (Disney) The Hangman's Revolution

The Hangman's Revolution The Atlantis Complex (Disney)

The Atlantis Complex (Disney) The Eternity Code (Disney)

The Eternity Code (Disney) The Fowl Twins

The Fowl Twins Artemis Fowl. The Arctic Incident af-2

Artemis Fowl. The Arctic Incident af-2 Artemis Fowl and the Atlantis Complex af-7

Artemis Fowl and the Atlantis Complex af-7 Artemis Fowl. The Opal Deception af-4

Artemis Fowl. The Opal Deception af-4 Artemis Fowl. The Lost Colony af-5

Artemis Fowl. The Lost Colony af-5 Airman

Airman Artemis Fowl af-1

Artemis Fowl af-1 Artemis Fowl: The Eternity Code af-3

Artemis Fowl: The Eternity Code af-3 Screwed dm-2

Screwed dm-2